Виділіть її та натисніть Ctrl + Enter —

ми виправимo

Rocking on target

In order to understand the way Putin mechanism of “the Third Maidan” creation works, let us see how the Ukrainian newspapers report the latest events. (Abbreviations: AiF for “Argumenty i Fakty v Ukraine” (Arguments and Facts in Ukraine); KP for “Komsomolskaia Pravda v Ukraine” (Komsomol Truth in Ukraine)).

1. Just a little more panic

Inflation processes are known to be significantly influenced by social psychology. Mass buying up of foreign currency, consumer market fever as well as apocalyptic speculation strongly influence currency trading, currency turnover, and, as a result, the rate of exchange.

The monitoring of the Ukrainian press of February 25-27 makes us come to the conclusion that some of the periodicals were not so much reporting the economic problems and consumer hysteria, as forcing the hysteria to escalate. The emotional vocabulary and agitating headings are used. “The psychologist explained the reasons of food panic” (KP, February 27); “Flour and butter snapped up” (“Segodnia,” February 26); “What has not went up yet” (“Vesti,” February 27) – that is how the headings are formulated at the leaders of our newspapers.

Under the headings, image-bearing descriptions of panic are presented. What is more, the authors actively use generalizations and hyperbolas, a well-known tool to make a problem seem bigger than it really is. “Panic in the markets (Is it really in every market?), currency can be bought only from moneychangers (Was the situation different a month ago?), while the roads are deserted (Are they empty at all?)” (“Segodnia”, February 27, p.1); “People (??) throughout the country(??) are rushing to spend the last hryvnias to buy food and technical appliances” (AiF, February 25, p.1); “The market stalls are empty – sugar, flour, and cereals are snapped up. For example, in Lviv, people mostly snapped up loose cereals and vegetable oil by packages. The same situation is in Uzhgorod: people were storming the supermarkets” (“Vesti”, February 25, p. 4). In the meantime, they give advice on how to panic correctly: “In social networks, they actively recommend to lay in a supply of imported household chemistry, including detergents, soap, toothpaste, and even tights that also went up two-fold yesterday.”

More and still more emotions! - that is the principle the press seems to follow faithfully. “Back in 1990s. Diving hryvnia, rising petrol, and market fever. The main subject of the previous week was hryvnia rate madness” (“Segodnia,” February 27, p.2). Meanwhile, AiF shines with a depressive horror style: “… slimy like a nightmare and black like the unforgettable Tuesday the rumour was: default” (AiF, February 25, p.1).

Speaking of 1990s, reminding the citizens of hard and crisis years, coupons and millions on worthless papers is becoming one of the key-notes. On February 25, it was mentioned by AiF (a headline on the leader was “A portal to 1990s”), while on February 27, it became the main subject of “Segodnia” and was mentioned in “Vesti” while citing an anonymous deputy (p.3). There is obviously something about that: an appeal to dangerous and unpleasant experience makes you worry about your security and try to reduce possible negative outcomes. In what way can you do that? Right, buy everything as long as it is cheap.

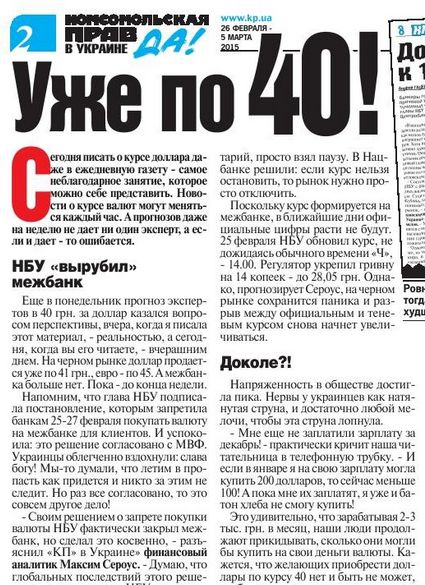

In order to escalate emotions, media use rumour and unverified data. On February 26, KP reflects upon the influence of hypothetic 40 hryvnia-to-dollar rate on the country’s economy. “Many [financiers] concede dollar’s rise, although they do not dare to suggest it openly: according to the most pessimistic forecasts, the rate can reach 36 hryvnias per dollar, while by the most optimistic forecasts the rate will be 34.0-34.5 hryvnias per dollar” (“Vesti,” February 27, p.2); “Rumour has it, they will introduce food ration tickets. As a result of the rumour, the food panic grew” (“Vesti,” February 25, p.4); “Answering “why all this hysteria?” every mother’s son said: “Dollar is growing. Pricetagsarechangedeveryday. Today I buy loose sugar for 15 hryvnias, tomorrow it may cost 30. I’d better have all that at home, it won’t get spoilt” (KP, February 27, p.6); “Yesterday the rate was 25, tomorrow it will be 35…” (AiF, February 25, p.1).

By spreading rumour and emotions and describing generalized and specific images of panic, the newspapers begin to function as twaddle at the kitchen or a street gossip, just million-scale.

By using frightening and emotionally saturated wording, the media cultivate fear and sense of danger among the readers. By emotional demonstration of social panic, they spread these emotions among their readers; they spread panic rumour and behavioral patterns. By generalizing panic moods and extending them from separate citizens to the entire society, the newspapers create a virtual reality, in which hysteria absorbs everyone, so that the readers have no other behavioral pattern to choose.

2. Who is to blame?

Fear, sense of instability and danger, growing frustration, tension and tiredness result in a natural wish to get rid of the source of discomfort, and to do it as soon as possible. Aggression grows, and all the flow of social negative will be directed at the search of the one to blame.

This is where it’s all at. Obviously, there would be no catastrophe if there were no war. Our government and National Bank of Ukraine do provoke a lot of complaints, but such a breakdown could hardly be possible in peaceful times. In fact, war and crisis are the same subject, which should be scrutinized just in this cause-effect relation (with officials’ errors as an additional factor as well). It should be so, but reality is often different.

Citizens’ emotions are actually a powerful weapon in the war between Russian and Ukraine. Spontaneous, uncontrolled mass emotions are a spear in the middle of the arena, and the key question is who will be the first to grab it and heat the target. I.e. the question is who will take the social hate under control and aim it at the enemy. Ukraine is likely not to lay a claim at this spear; otherwise, it would mean propaganda, which is allegedly beneath our democratic dignity. So, the answer is clear.

The newspaper “Vesti” avoids mentioning the war as the reason for crisis. One of the uncommon notes is found in Fesenko’s quotation, in which only 20% of influence are given to the war, while “government’s fault part is 60%” (“Vesti,” February 27, p.3). Yatseniuk’s government responsibility for the economic breakdown is well visualized: the heading “Prime-kamikaze. Ayearinpower. Itcouldbeworse. Perhaps” is placed next to the photos of petrol prices and infographics dealing with prices hike through the year. “By Azarov, 180 milliard hryvnias were printed in four years, while by Yatseniuk 200 milliard hryvnias were printed in a year. We need to remove this government,” the newspaper informs, citing an anonymous official.

“Donbas: A New Attack. By prices and deficit” isa heading in “Vesti” of February 27, p.4. The crisis as a Kyiv’s weapon is yet an interesting version. On February 25, there is a page-wide heading “40 hryvnias for $1 at the black market,” whereas the next page informs: “New asphalt in Donetsk.” Isn’t that unfair?

The newspaper “Segodnia” of February 27 is not so much treating the war as a reason for crisis, as directly putting the blame for all the sorrows on the government. Crisis is treated as the consequence of the National Bank’s actions (page 3 contains a large set of advice for the regulator on how to work properly) and the consequence of political instability (page 3 has an article “The outcomes of the policy: Sausage and Coalition”), but not war. Moreover, “post-Maidan” power is to blame even for the war itself! “Whatever they initiate, the outcome is just inflation and economic breakdown,” Buzina, the chief editor of “Segodnia” (February 27, p.2), claims: “No cardinal improvements in a year after Maidan. Itonlywentfrombadtoworse. By Yanukovich, there, at least, was neither inflation nor mobilization.” Placing the responsibility for all the evil on Kyiv tends to associate with Kiseliov…

A day before, on February 26, the newspaper attacked Yatseniuk as well. “Hryvnia’s stability is one of Yatseniuk’s unfulfilled promises” (“Segodnia,” February 26, p.3). The analysis of the prime-minister’s mistakes that have led to inflation follows (on the behalf of anonymous “economists”). It goes without saying that the war as a reason for inflation was ignored again. (In fact, the war as the reason for the crisis was mentioned in the two issues, of February 26 and 27, only in Okhrymenko’s quotation).

The pattern in AiF is a bit different. The issue of February 25 has two articles on the impact of war on the economy. KP, however, follows the trend chosen by “Vesti” and “Segodnia.” “The National Bank “turned” interbank and made hryvnia collapse” is a heading in the issue of February 27, p.2. On February 26, p.2, the article “Already 40!” with frightening infographics is followed by another one: “One year as two: What has changed in power since the Maidan revolution,” gently hinting at the direct association between the two events. The war as a reason for the crisis is ignored again.

Excluding war as a reason for economic breakdown and inflation in Ukraine from media discourse as well as placing all the responsibility on Kyiv authorities create favorable environment for people’s unrest and dissatisfaction with the power, which is traditional for the Ukrainian society. Along with general latent dissatisfaction because of absent reforms, stable corruption, lack of tangible democratic advance, and active propaganda are really paving the way for protest moods.

3. “The Third Maidan” as a virtual reality

Meanwhile, transition from moods to actions is only a matter of technology. First and foremost, the society is to be internally prepared for a new Maidan.

Actually, there is nothing to prepare, because it is already prepared. While you’re sitting in your apartment, there is almost revolution outdoors. “Howlong?!” is a subheading in KP of February 26, p.2. “The tension in the society is at its pitch. The Ukrainians are just a bundle of nerves. Any trifle will be enough to make them burst.” Be ready, they will give a sign. “How long will it last? Who buys foreign currency for today’s price?”; “In the lobby, the annoyance with the government that is unable to stop economic breakdown and hryvnia’s diving is growing.” (“Vesti,” February 27, p.3).

In fact, there is enough reason for hate. For example, in “Vesti” of February 25, p.4, the scathing materials about prices and currency go along with the news on how “a woman was fired for the ribbon of St. George on a poster.” You see, what the power is actually busy with.

Let alone the ribbon. “Segodnia” of February 27, p.2 carries screaming headlines that speak for themselves:

- Back in 1990s

- MiddleClass: “We’llcookbyourselvesandrefuseelitealcohol”

- Foreign trips will be cut: our south and the Carpathians will be an alternative

- An automobile is luxury again: the jams are almost gone, and “iron horses” will be fed with gas

- We buy shoes of home manufacture and clothes sold in flea market or second hand

- Repressions for a dessert.

Buzina proves that our power authorities are “latent Stalinists,” “a firm hand,” and carry on “exhibition lawsuits against the ‘ex’;” there are parallels between them and Stalin, and all in all, the Soviet dictator is at least not worse because he had carried on a genocide under economic growth (could it make death for millions of people easier?). “Eating “public enemies” will not make you full,” the newspaper’s editor is shaking his fist at the Pechersky hills.

Whoops! Here we get such a surprise: “a financial Maidan.” No matter how large in number it was, as Maidan 2014 began with a student demonstration as well. The term “financial Maidan” itself (which was worked out long before February events) is rather profitable for propaganda: Ukraine is yet in fever! The power is acting correspondently. “Militia tried to disperse “Financial Maidan” in a violent manner,” “Vesti” of February 27, p.2 inform. “…The rioters were attacked by militiamen…;” “We were beaten by sticks. Evenwomen. Three of them were taken to emergency.”

“Disperse of the protest action resembles the actions of militia under the previous power,” KP of February 28 writes.“Whatasteadysenseofdéjà vu! Militia, rioters, force, sufferers… The militiamen try to justify themselves by “perturbation.” So, the events of the previous years are immediately coming up” (KP, February 28, p.4).

This is how we plunge into a virtual world, in which Ukraine is a bubbling pot of social unrest, already bursting in spontaneous protests. These protests are suppressed by an authoritarian power, so the future of this power will be the same as for the previous one. You and I, in turn, are expected to cheer this process to the echo.

Doesn’t it remember you anything? The Crimea’s annexation by Russia and Donbas’ independence were firstly virtual, too. Nobody believed it. But today media space does not reflect the reality anymore. Instead, it has begun to actively create it.

The economic breakdown in Ukraine is now not only a challenge for our economy and finance. It is a colossal danger of information war, which is now defining the real one. A common disaster could unite the society and mobilize its forces against the enemy that has imposed this war on us, bringing it to each of us either as call-up papers or as defaulted salary. But for that end, someone should take responsibility for that in our country.

In turn, we are creating new ministries and go on disputing ourselves hoarse on how to win the information war without getting stuck in propaganda. All the while, rocking of the country is on target.

The monitoring of Russian propaganda is performed within the project implemented by the NGO Telekritika under support of Internews Network.